Roger Ebert was arguably the most famous American film critic of all time. Known for his countless witty and insightful film reviews in the Chicago Sun-Times, as well as for the TV program At the Movies, which he hosted alongside fellow Chicago film critic Gene Siskel, Ebert remained one of the most entertaining and well-respected critics among the film-going public for over four decades before his passing in 2013. Nevertheless, Ebert was not afraid to dissent from the consensus opinion of his fellow film critics if a film did not appeal to him.

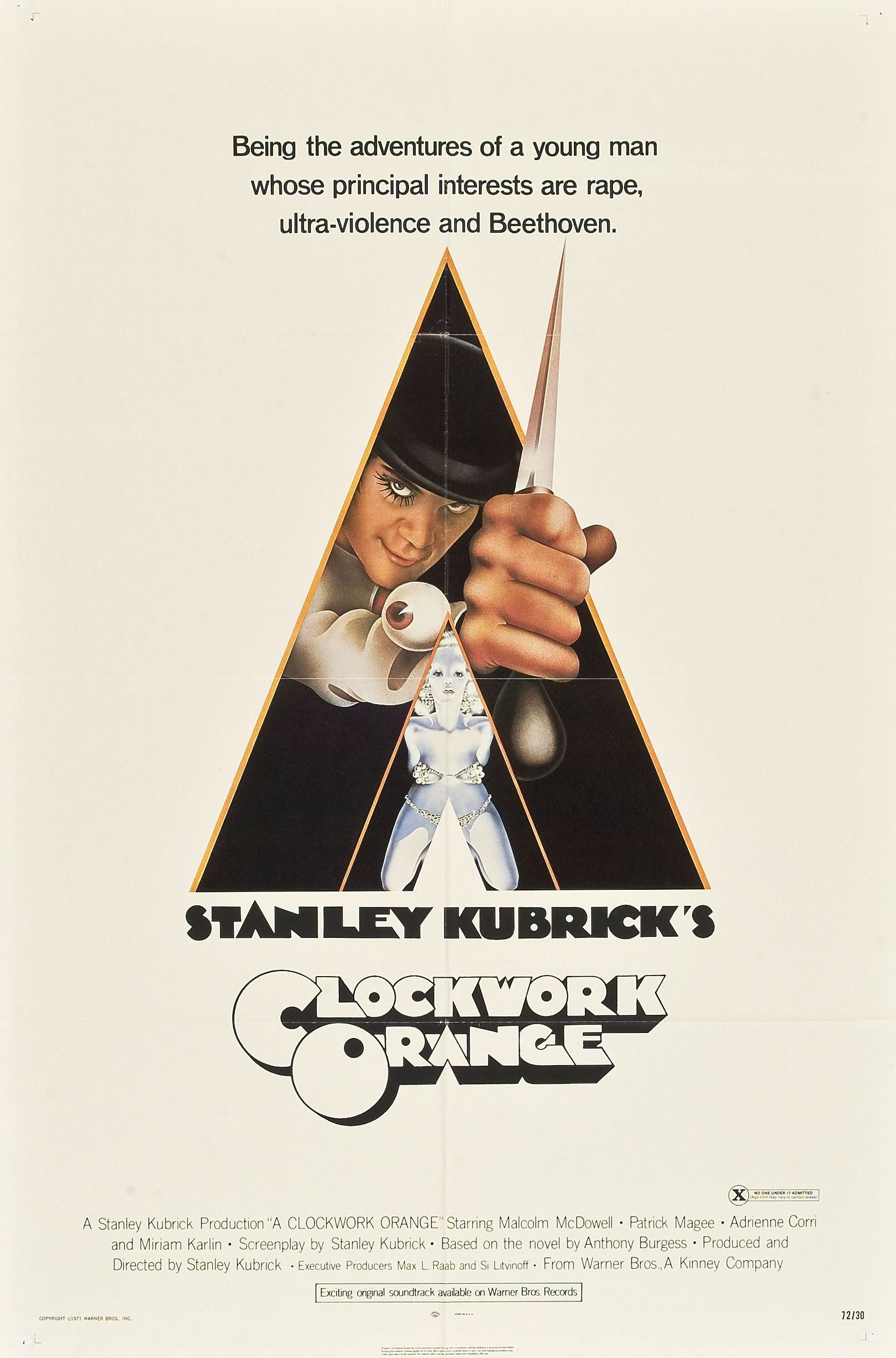

One of the most prominent examples of this was his review of Stanley Kubrick’s controversial sci-fi classic, A Clockwork Orange (1971), to which he only awarded two stars (out of a possible four). Specifically, Ebert took issue with what he felt were the film’s troubling political messaging and the empathetic portrayal of its disturbed protagonist, Alex (memorably played by Malcolm McDowell). But was Ebert correct in his condemnation of A Clockwork Orange? Or did the normally astute, Pulitzer Prize-winning critic miss the mark for once?

Roger Ebert Was Not Alone in His Discomfort with the Film

A Clockwork Orange is an adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ 1962 dystopian novel of the same name and was written, directed, and produced by legendary filmmaker, Stanley Kubrick. The film tells the story of Alex DeLarge (McDowell), a British teenage delinquent who embarks on nightly escapades with his gang of “droogs,” in which they partake in what Alex calls “ultra-violence,” including rape, assault, and robbery. But when Alex is finally caught by the police, he is subjected to a controversial form of therapy by the British government that is intended to prevent him from ever committing another crime.

Related

All That We Destroy: How Into the Dark Updates A Clockwork Orange

All That We Destroy is part of the Into the Dark horror anthology that serves as an update to the classic A Clockwork Orange.

The film’s subject matter was so disturbing that it was initially given an X rating in the United States and was outright banned in several other countries. In the UK, A Clockwork Orange was accused of prompting copycat violence; Kubrick voluntarily removed the film from British theaters due to the backlash, the tabloid press, and, according to his wife, death threats against him and his family. Many critics and viewers were disgusted by the film’s violent content, the degree of which was unfamiliar to most audiences in 1971, before the “video nasty” era there. The fact that the film forces the audience to share the perspective of the sadistic young Alex for its entire runtime only polarized its reception even further, and arguably formed the primary basis for Ebert’s criticism of it.

What Did Ebert Say About ‘A Clockwork Orange?’

In the opening sentence of his review, Ebert describes A Clockwork Orange as “a paranoid right-wing fantasy masquerading as an Orwellian warning,” and he ends his review by dismissing it as “talky and boring.” He argues that, while the film presents itself as “oppos[ing] the police state and forced mind control,” all it ends up doing is “celebrat[ing] the nastiness of its hero, Alex.” As bold as this accusation is, Ebert backs it up by accurately pointing out that, aside from his criminality and his love of Beethoven, there are no other defining traits to Alex’s character. Furthermore, according to Ebert, “No effort is made to explain [Alex’s] inner workings or take apart his society.”

Related

15 of the Most Nihilistic Movies Ever Made

These nihilistic, thought-provoking films have received so much praise, despite being pessimistic and amoral, that they are definitely worth a watch.

In lieu of a more complex and in-depth study of Alex’s sadism, Ebert deduces the film’s message to be that “Alex is violent because ‘society offers him no alternative,'” an explanation which he finds shallow and trite. Ebert even points to some of the film’s technical elements as evidence that the film whitewashes Alex’s depravity in order to make him seem more sympathetic. For example, Ebert notes Kubrick’s frequent use of wide-angle lens in several shots throughout the film, which distorts the shapes of objects at the edge of the frame while keeping Alex’s normal shape in the middle. Ebert argues that “this encourages us to see the world as Alex does, as fun-house mirrors of weird people out to get him.” As such, “a visual impression is built up…that Alex, and only Alex, is normal.”

What stands out about Ebert’s critique of A Clockwork Orange is how he seems to treat the film’s depiction of Alex as a zero-sum game. Because the audience is made to empathize with Alex when he is psychologically tortured by the government in the film’s second half, Ebert claims that the film fails to adequately condemn his grotesque actions in the first half. But perhaps Ebert overstates the degree to which the film aligns the audience with Alex.

After all, even if it is true that the film’s camerawork forces the audience to see society through Alex’s eyes, it doesn’t necessarily lessen their repulsion at his violent acts, which Kubrick films with uncompromising intimacy. Indeed, being forced to share such a monster’s perspective might just as easily make some audience members more scared of him, not less. (Indeed, this is the case in some horror films, such as Angst, Maniac, American Psycho, and the recent In a Violent Nature).

Moreover, even as they try to curtail Alex’s violent impulses, the police, government, and medical institution in the film are repeatedly shown committing violence themselves for political gain. Perhaps it makes more sense, then, to see the film as condemning Alex and the state equally, rather than whitewashing the former to demonize the latter, since both of them rob people of their bodily autonomy and safety.

9:27

Related

Roger Ebert’s 10 Favorite Movies of All Time

The great film critic Roger Ebert once sat down to write a list of not “the best” movies ever made, but his favorites of all time.

Is Roger Ebert Wrong About ‘A Clockwork Orange’?

Given that Roger Ebert’s opinion of A Clockwork Orange contradicts the critical consensus of the film, it might be tempting to simply dismiss his assessment of the film as wrong and misguided. However, making such a blanket statement feels overly reductive. After all, film, like every artistic medium, is subjective. And even though Ebert’s job as a professional film critic required him to keep an open mind and have an eclectic taste in all kinds of films and filmmaking styles, he was still a human being with his own personal tastes and opinions.

In fact, Ebert’s willingness to honestly share his thoughts, even if they went against the popular view, was what made him such a respected critic. Likewise, a distinguished film critic disliking a film doesn’t mean that readers and viewers are obligated to dislike it as well — Ebert himself would be the first person to share this sentiment. You can see A Clockwork Orange for yourself by renting or buying it on digital platforms like YouTube, Apple TV, Google Play, and on Prime Video through the link below:

Watch A Clockwork Orange

Source link

Add Comment