Liverpool’s ticketing system has turned into a digital scramble and the next generation is at risk of being shut out of Anfield, writes Peter Bolster.

Football clubs weren’t simply created to fill time on a Saturday afternoon. They sprang up in churches, workplaces, and cricket clubs—part moral project, part social lifeline, part declaration of belonging.

Over time, they became the beating hearts of working-class towns, places where you showed up week after week to stand shoulder to shoulder with your neighbours and feel like you mattered.

Matchday wasn’t supposed to feel like a digital scramble or an exercise in brand loyalty. You didn’t need an app to prove you cared. You went because it was yours — because it was the most human thing in the world.

For generations, that sense of belonging was passed down: dads taking their kids, mates sharing spares, young fans getting their first ticket because someone trusted them to carry it on.

Now, that inheritance is being lost. Rules and systems have made it almost impossible to share what you love, and the game that once thrived on community has been hollowed out by algorithms, loyalty thresholds, and corporate suspicion, until supporters are treated less like people and more like accounts to be managed.

My personal experience

My experience is a perfect symbol of how clinical the club has become. I was grieving the death of my sister, 28 days in intensive care before we lost her in April 2024.

During that time, in my fog of grief, I forwarded a couple of tickets I couldn’t face attending to my son. And in that state, I made a mistake and forwarded one too many. One of the games I actually did attend (Nottingham Forest) ended up being credited to my son, whose ticket was on my phone.

An easy mistake, you might say.

I explained the situation to the club, offered proof, and even said I would provide a death certificate if necessary. All I received was a cold email with no condolences, not even an acknowledgement. Just another request for more evidence.

That’s what this system has become — heartless, inflexible, dehumanising. The club asked me to prove I was there, share a bank transaction, and explain exactly how I accessed the stadium.

Eventually, after weeks of pushing, I had my 13+ status reinstated. But why did I have to fight so hard during a family tragedy? How many fans in similar situations would simply give up?

A system that breaks its own rules

When the club decided that credits would follow the attendee, not just the purchaser, many fans accepted it. It was a reasonable move to clamp down on touting, but with a caveat.

Supporters asked for allowances to remain in place for life events: the ability to distribute tickets a couple of times a season, or to deal with late fixture changes. Those safeguards have now been stripped out.

The ‘Friends & Family’ cap of 18? Another example of punishing loyal supporters for the club’s own technological failings. People have been raising this issue with the club since before COVID.

But instead of investing in IT systems or nuanced checks, they’ve gone with the sledgehammer again. Long-time members who buy tickets on behalf of elderly parents, children, or mates in recovery are now facing an ultimatum: adapt or get locked out.

Liverpool FC making decisions for match-going supporters is like think tanks setting policies for people in council estates: no understanding of the reality, no empathy for what it actually means.

This isn’t stopping touts — it’s driving regular fans underground, using burner phones and second accounts just to keep up. It’s happening already, and these changes will only accelerate it. Meanwhile, organised touts with resources will continue to thrive — they always find a way.

Loyalty without compassion

The credit system is supposed to reward loyalty. But right now, it feels like it’s punishing humanity.

Supporters who miss a few games due to job loss, illness, pregnancy, or bereavement are treated like they’ve failed a test. There is no flexibility, no recognition of decades of service.

One off-season, and you fall behind permanently. The climb back is nearly impossible — especially with the club’s decision to group fans with 8+ credits into the same pot as those with 4+. Yeah, that went under the radar in the last few years.

Where’s the fairness in that? How can we expect people to stay engaged if one life event puts them at the back of the queue forever?

And let’s be honest: if you have enough money, you can still buy yourself into the 13+ group. The corporate packages and premium hospitality tickets count towards your credits exactly the same as a standard match ticket—provided you give them your Supporter ID.

So if you’re willing to pay thousands for lounges and executive seats, you can skip the queue and call yourself loyal, even if you’ve never stood in the Kop or queued on a freezing morning.

That’s the reality of modern football — where loyalty isn’t measured in years or memories, but in how much you can spend.

The next generation shut out

One of the most worrying outcomes of this system is the knock-on effect on the next generation of fans.

If you’re a season ticket holder and you want to take your child to a game, good luck. You can’t buy a child’s ticket unless you’re in the same sale, and young fans building credits aren’t in the 13+ or season ticket pot.

That means many parents are being forced to create another adult membership just to sit beside their child. And if they do manage to get both tickets, the parent often has to give up their original seat — likely one they’ve had for years — just to make it work.

This isn’t just inconvenient. It actively disincentivises passing down the tradition. It tells fans: ‘you’re on your own’.

And it’s not just league matches. Even the Auto Cup Scheme — once a reliable way for loyal supporters to secure their place at every home cup game — has become oversubscribed. Now, you see fans who’ve been to every domestic and European cup tie for the last 10 or 15 years suddenly unsuccessful in a ballot. How does that happen?

Why is there even a ballot for something that was designed to reward consistency and commitment? It feels like yet another sign that no matter how long you’ve been part of it, nothing is guaranteed anymore.

So what should change?

Let’s be clear, no one is expecting miracles. There are only so many seats in Anfield. Demand has never been higher, and nobody is asking the club to magic up 10,000 extra tickets.

But there are smarter, more humane ways to approach the problem. Instead of defaulting to suspicion, inflexibility, and punitive technology, Liverpool could adopt a more balanced system that protects the integrity of ticketing without sacrificing the community it’s supposed to serve.

One place to start would be introducing a rolling three-year loyalty window that accounts for life events and creates a buffer for genuine supporters.

If someone has to miss a season because of bereavement, illness, or job loss — like I did — they shouldn’t lose all their credits in one stroke. Recognising long-term commitment without penalising ordinary setbacks would show that loyalty is more than a box-ticking exercise.

The club could also restore limited distribution rights to help supporters cope with midweek fixture changes, childcare, illness, and emergencies. Bringing back the option to forward a small number of tickets each season without fear of punishment would give people the flexibility to plan around real life without feeling like criminals.

Simple measures like trialling evening and weekend sale times would make a meaningful difference to working-class supporters. At the moment, sales often happen during weekday mornings when many fans are at work. Offering alternative windows would help those who can’t sit by a computer mid-shift or take time off to queue online.

Creating a proper local sale at the ticket office — not just as a PR gesture but as a genuine commitment to the city — would keep matchdays accessible to local supporters rather than dominated by online sales and tourism. Allocating a percentage of tickets for Liverpool postcodes, sold in person, would be a powerful statement about who the club really belongs to.

The ‘Friends & Family’ system also needs reform. Instead of capping the number of linked accounts at 18, the club could use intelligent software to flag suspicious behaviour while still allowing genuine supporters to help elderly parents, children, or mates who rely on them. It’s possible to protect the system without punishing everyone.

Other changes could ease unnecessary stress. Making final ballots earlier and fairer would give clarity and reduce the financial burden on fans who travel. Announcing results with more notice would help people avoid booking expensive trains or hotels they might have to cancel at the last minute.

Introducing a consistent seat allocation system for members, similar to the Auto Cup Scheme, would allow fans to sit in the same place all season and build the bonds that make Anfield special. In the same spirit, the club should make it easier for groups of friends and families to buy tickets together.

People don’t want to go alone or be scattered across the ground. A better group booking option would restore the social side of football that built this club in the first place.

Finally, Liverpool should use the identity information it already holds to protect the system intelligently. Every supporter has been asked to provide photo ID and prove who they are.

There is no excuse for blanket suspicion. That data should be used to build trust with genuine fans and focus enforcement on the minority manipulating tickets for profit. Smarter, targeted approaches to tackling touting — like monitoring accounts with dozens of different names or constant reselling — would be far more effective.

Even the passport office does spot checks without treating everyone as a criminal. Fans would accept proportionate measures if they were applied fairly and transparently, rather than seeing the entire supporter base punished across the board.

The final word

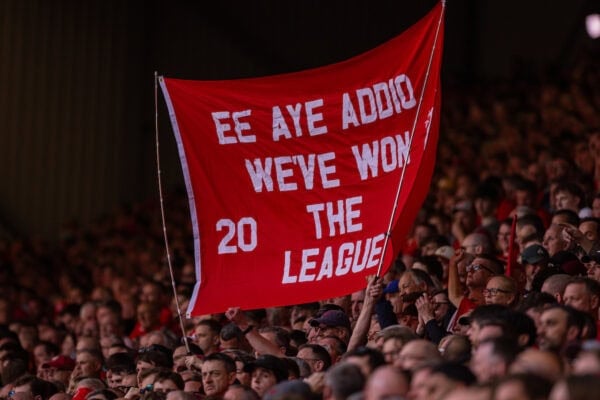

The club, Sky Sports, the Premier League – they all market the atmosphere. They sell the spectacle of us. But if these changes continue, what kind of crowd will be left? What kind of supporter culture are we cultivating if every match feels like a battlefield just to get in?

Gareth Roberts put it best when he spoke on The Overlap, highlighting how the game is drifting further and further away from ordinary people. He talked about how, for generations, football was built on community, working-class identity, and the idea that the match belonged to everyone.

Now, he said, it feels like the sport is becoming something you simply watch on television because you’ve been priced or locked out.

He asked the question that should haunt every decision-maker: “What type of fan do you want in the ground?” Because make no mistake, these changes are shaping the answer.

Liverpool isn’t just a club. It’s a living story.

It’s pain and joy and unity and heritage. The club must remember that. Because this isn’t just about process — it’s about people. And if that gets lost, we all lose.

Source link

Add Comment