Content for anime can range from comfortably familiar to wildly disorienting. Some works deliberately push past style andtraverse visual territories that can feel dreamlike, rough, or just downright nonsensical. The titles below sit comfortably in this category.

These anime challenge readers by refusing tidy explanations while rewarding attention with strange imagery, tonal shifts, and storytelling that resists conventional narrative. Some lean more towards philosophy and ideation, while others favour feverish visual invention, and the rest prefer to use absurdity as a tool for focus. However, these titles are not novel simply for the sake of it.

Within each series are hard, uncomfortable questions that force the viewer to answer through feeling rather than exposition. For the unfamiliar fan, approaching these series expecting straightforward entertainment will leave you at the very least bewildered.

Bobobo-bo Bo-bobo (2003)

Created by Yoshio Sawai, Bobobo-bo Bo-bobo presents absurdist comedy. The series attacks shonen tropes by refusing to follow them. Its plots dissolve into pun sequences and visual contrapositives while the characters wage epic battles using hair-based powers and surreal transformations.

Still, beneath what might read as juvenile chaos, an exacting comedic rhythm is revealed. Relying more on timing than sense, its gags build on prior nonsense and then subvert expectations with renewed silliness. The show also performs satire: by blowing shonen genre conventions to cartoonish scale, it exposes their underlying rigidity.

Consequently, Bobobo-bo Bo-bobo is not at all subtle, but it is rigorous in its own terms. For viewers who enjoy deliberate chaos and disciplined absurdity, the series functions as a study in how comedy can be both anarchic and formally precise.

Cat Soup (2001)

Tatsuo Satō’s Cat Soup compresses surreal horror and lullaby logic into a short, silent fable. The story’s tiny runtime hosts a procession of images that move between playful and sinister without transition. It follows a childlike cat that enters a dreamlike netherworld where life, death, and meaning are handled as tangible objects.

The film’s absence of dialogue forces your attention onto its rhythm, sound, and visual metaphor, and it treats death as a surreal landscape rather than a moral endpoint. Cat Soup is brief, and its brevity increases its intensity, meaning that there is no time for comfort, only accumulation of uncanny tableaux.

It is not explanatory and does not offer solace. Instead, it offers a condensed experience that lodges in the mind like a bright, sharp fragment of dream memory.

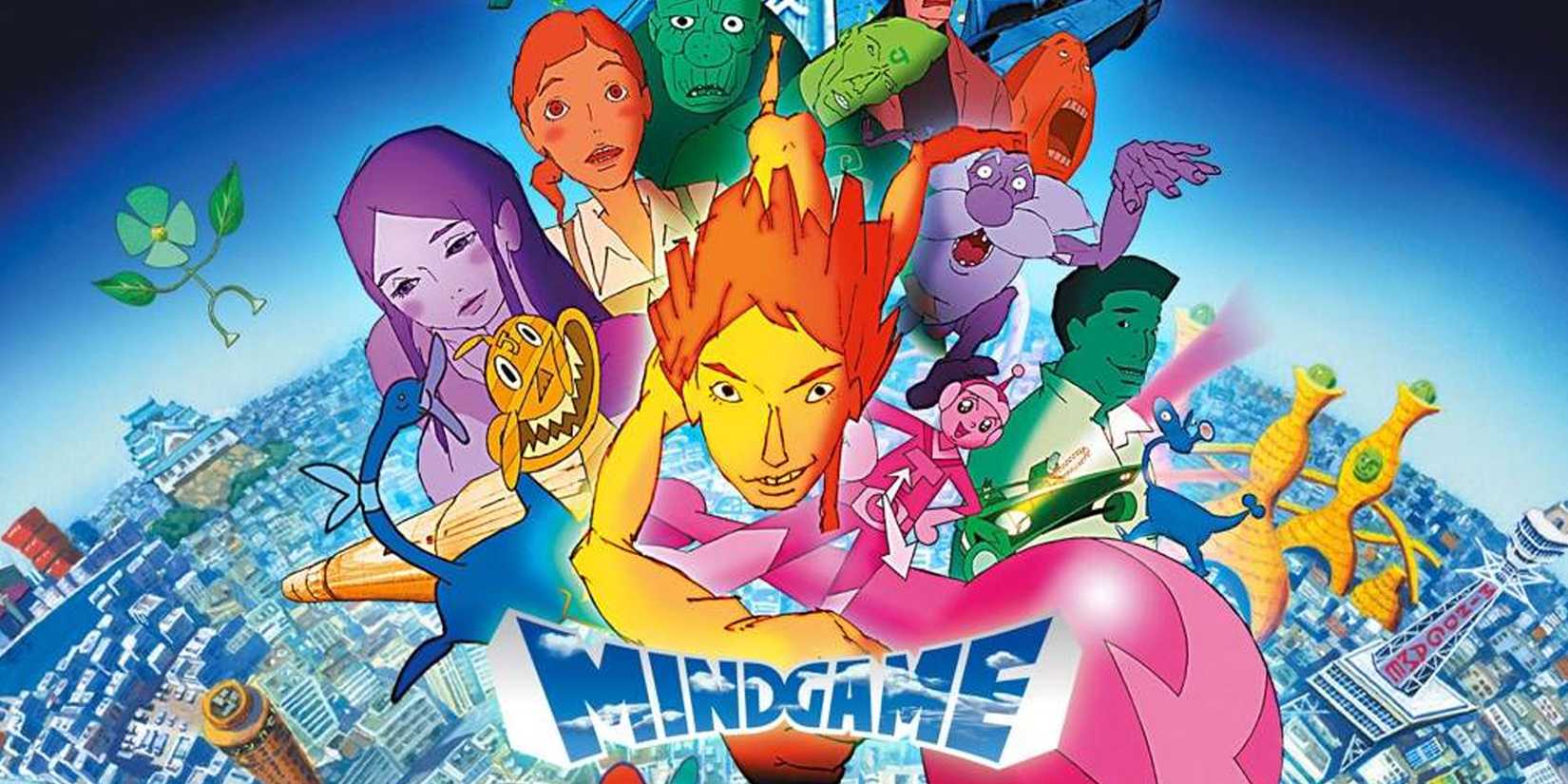

Mind Game (2004)

Based on Robin Nishi’s manga, Mind Game reads like an essay on radical freedom executed through ecstatic animation. Masaaki Yuasa’s film abandons conventional continuity for a collage logic that jumps scales, styles, and emotional registers. Characters spill out of bodies, memories become landscapes, and the rules of perspective change mid-argument.

Following the life of the 20-year-old Nishi, the film’s core proposition is simple: life’s value comes from choice and motion rather than safety. It stages an operatic escape from paralysis by transforming trauma into kinetic, visual invention. Technically, it is a tour de force: every frame experiments with line, color, and timing.

The film can feel exhausting and intoxicating in equal measure because it refuses to rest on a single visual identity. For viewers ready to be carried, Mind Game offers a rare blend of creative risk and heartfelt, messy optimism.

Dorohedoro (2020)

The brainchild of Q Hayashida, Dorohedoro combines grotesque humor with grim worldbuilding, resulting in an unexpectedly humane story of loss and recovery. The premise is blunt and rough: a city cursed by sorcery, a man with a lizard head, and a pair of sorcerers who must confront their own ethics.

The story details how the man with the lizard head, Kaiman, tries to recover his original face and his memories after being cursed by a mysterious magician. Surprisingly, the story finely balances graphic violence with tender absurdity. Characters who could be one-note villains display contradictory kindness, and the dialogue often alternates between crude jokes and sudden introspective insight.

On the other hand, the animation style foregrounds texture and grime, which makes the moments of tenderness feel surprisingly earned. In the end, Dorohedoro succeeds because it trusts tonal plurality. It allows grossness and compassion to coexist, producing a world that is both nasty and strangely generous in its moral imagination.

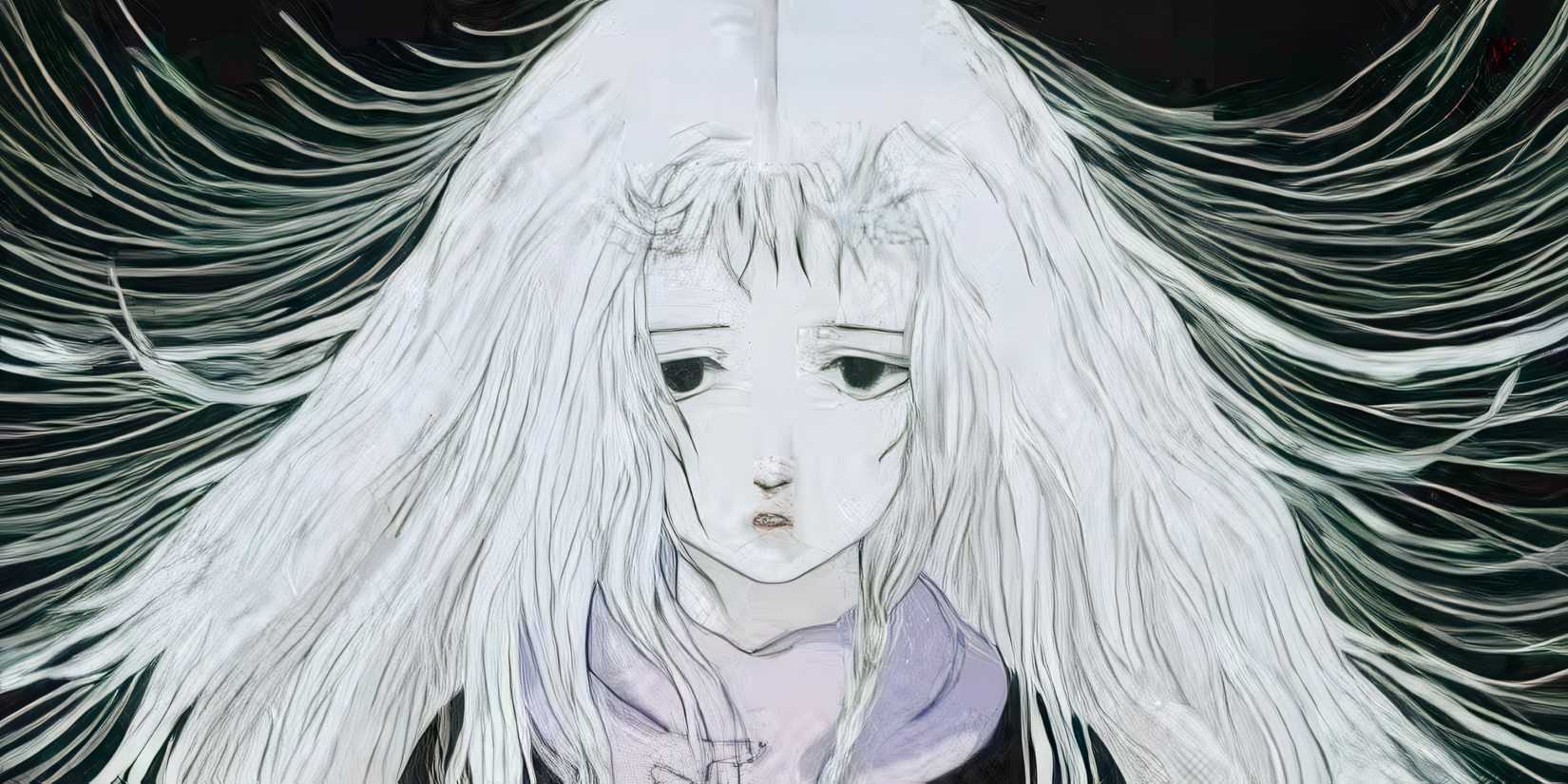

Angel’s Egg (1985)

Studio Deen’s Angel’s Egg is the kind of film that manages to resist a plot summary because its argument is visual and spiritual. It offers long, patient sequences that read like painted prayers interrupted by ruin. Featuring minimal dialogue and heavy biblical allusions, the film places a childlike figure and a wandering man in a primal landscape where objects carry theological weight.

Its imagery repeats and refolds, creating associative meaning rather than causal action. Director Mamoru Oshii intentionally invites interpretation without offering any resolution. As such, viewers must decide whether the film proposes redemption, ruins faith, or simply stages both. The soundtrack is both sparse and unnerving.

Truthfully, Angel’s Egg is not comfortable entertainment but a test of patience and openness that gifts a disquiet that lingers for days. Finally, the film’s stubborn refusal to explain itself is precisely the technique, treating mystery as a subject, not a trick.

Tekkonkinkreet (2006)

Tekkonkinkreet adapts a dense manga into a film that feels less like a narrative and more like a lived city. The film follows two orphans, Black and White, whose bond anchors Takaramachi city’s violent, mythic urban ecology. Director Michael Arias and the production team render the story’s cityscape with aggressive, hand-drawn energy that alternates between lyric tenderness and graphic brutality.

The film’s unusual mix of Western animation technique and Japanese sensibility produces a texture that feels fresh and slightly aggressive. Scenes fold memory into the present, and scale shifts without warning so that a rooftop chase can feel apocalyptic.

At its core, Tekkonkinkreet probes attachment and belonging: violence is both an external threat and an internal fracture. The movie refuses tidy catharsis because its power lies in immersion. You watch the city breathe and break, and the emotional consequences arrive organically through sound, shape, and the volatile bond of the two protagonists.

Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995)

Neon Genesis Evangelion presents a premise that combines mecha spectacle with personal psychological collapse, resulting in less of a genre entry and more of a psychological excavation of human consciousness. Its early episodes pose the conventional extra-terrestrial threats, but the series steadily shifts inward, turning battle sequences into metaphors for adolescence, anxiety, and existential dread.

Hideaki Anno’s direction blends silent, static frames with sudden, violent motion, creating intense shock contrasts. The characters are written with blunt flaws; their breakdowns are prolonged and often unresolved. The series’ later episodes trade the plot for interior logic and symbolic imagery, which not only divided the audience on release but ultimately secured the show’s reputation and legacy.

Essentially, Neon Genesis Evangelion changed expectations about what televised animation could risk. It asked audiences to tolerate ambiguity and to read suffering as subject matter, not a plot device.

Gankutsuou: The Count of Monte Cristo (2004)

Directed by Mahiro Maeda, Gankutsuou: The Count of Monte Cristo takes Alexandre Dumas’ classic revenge story and remolds it into one of the most visually daring anime ever to exist. Set in the year 5053, in a futuristic Paris rife with aristocratic corruption, the series tells a tale of betrayal, obsession, and retribution through a kaleidoscope of color and texture.

Immediately, the show’s art style stands out, a style you cannot help but admire. Detailing patterns that move independently from character outlines, every scene has a surreal, painterly quality that feels more like a living art installation than traditional animation. Yet beyond its visual complexity lies a story with a deeply emotional core.

Count Edmund Dante’s revenge unfolds like an opera, with beauty and tragedy shared in equal measure. Ultimately, Gankutsuou isn’t just simple strangeness; it’s a meditation on class, memory, the weight of emotions like vengeance, and their consequences, from a visually extreme perspective.

Source link

Add Comment